Like a Labyrinth

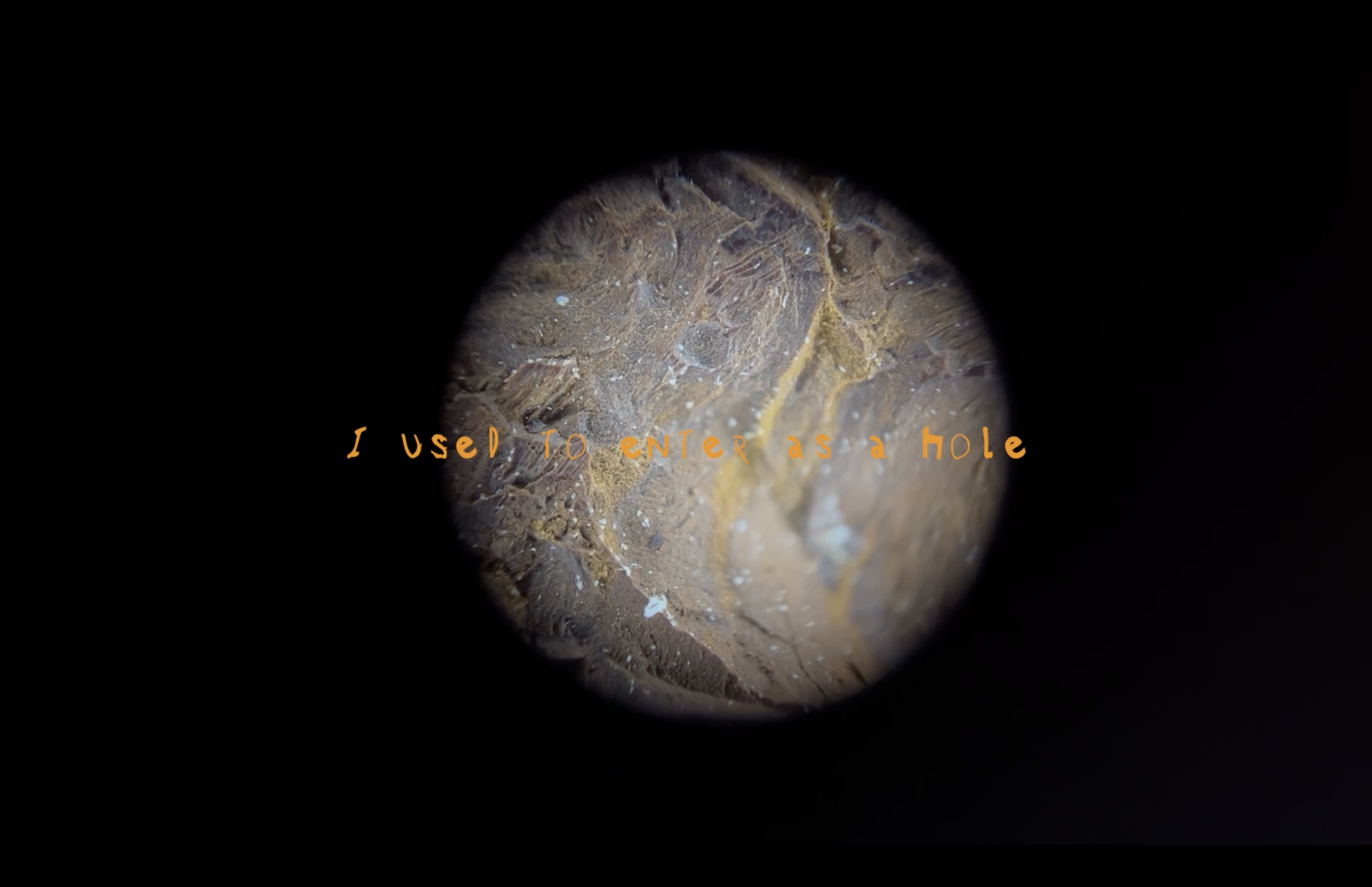

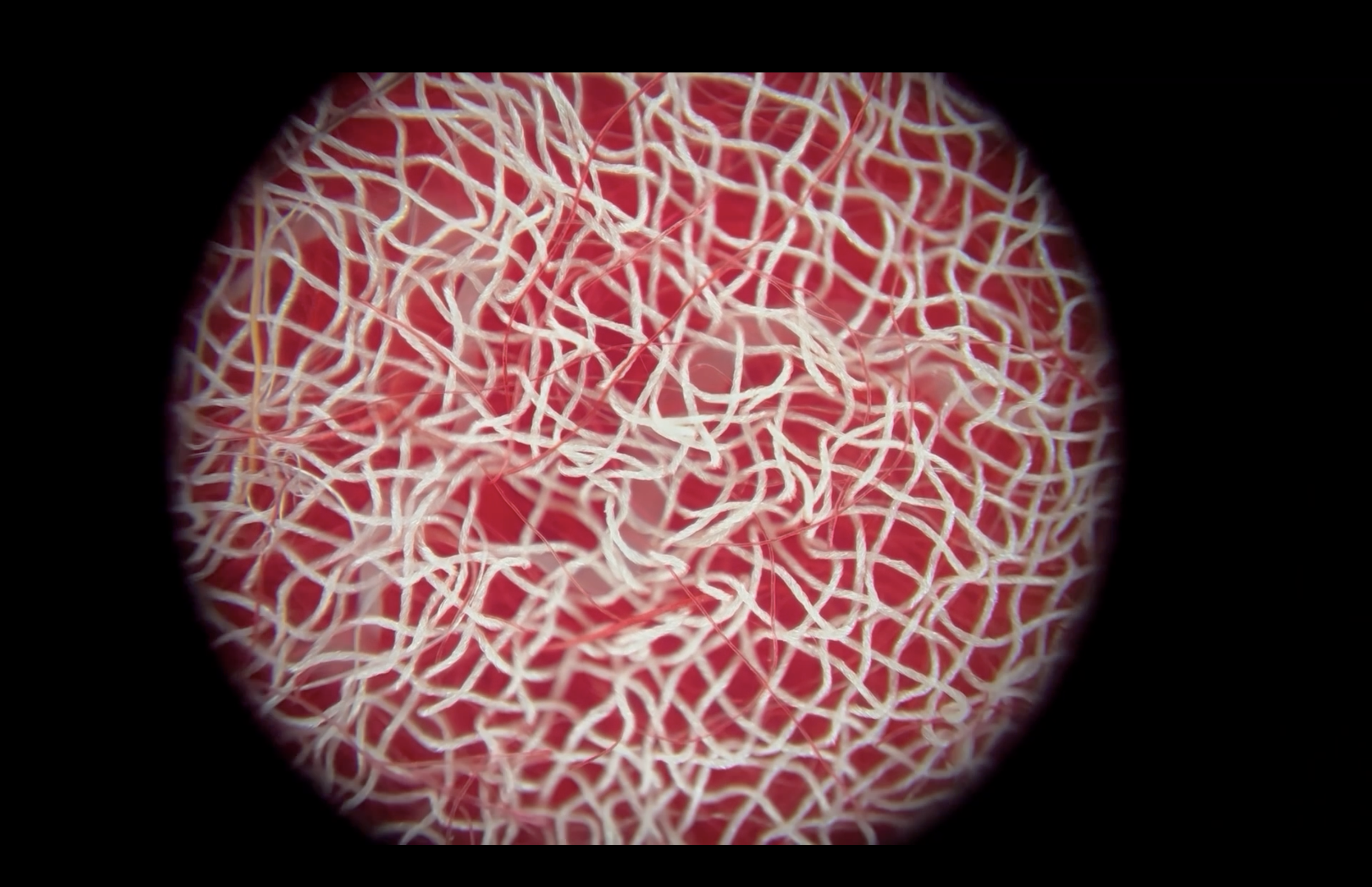

Edges, everywhere. Edges between bodies (skin), species (genome), ideas (ether), terrain (dirt). Every hole has an edge. Every whole, a limit. Every individual, their boundary. Every nation, its border. Every centre, its periphery. Edges are said to define; however, upon closer inspection, we see that edges don't bind, they connect. It's ambivalence at the edge that Like a Labyrinth explores. Drawing from the Minoan myth's architecture of disorientation, integrates 360 degree video with poetic verse and experimental sound design to create new myths of corporeal and ecological intelligence.

“Like a Labyrinth queers our perception of self and other, land and body, drawing attention to the constant and awkward adjustments of the perceptual apparatuses that define our boundaries. I hope you appreciate as much as I do this moving meditation on the edges between things, and how they come to be perceived — habitually, arbitrarily, and culturally.” — Alex A. Jones, Queer Ecologies Research Collective

Title: Like a Labyrinth

Year: 2025

Length: 21:32

Writing, Editing, Direction: Darian Razdar

Sound Recording: Luisa Ji

Gear: Simón Rojas

Producer: UKAI Projects

Location: Ferme Lanthorn

Sponsor: Canada Council for the Arts

The artist’s essay is published alongside the film’s release:

Hole

Since Einstein’s theory of general relativity, which predicted the existence of black holes — cosmic foci where gravity is so intense that no matter or energy can escape — the hole-idea has circulated and evolved prolifically. Stephen Hawking elaborated the physics of black holes, showing how these regions of space-time radiate energy randomly. It is this absolute concentration of mass that gives black holes their characteristic brightness at the center of billions of galaxies. As Hawking writes, “Black holes are not really black after all: they glow like a hot body, and the smaller they are, the more the more they glow.” The paradox of the black hole as a hot body of pure nothingness and concentrated everythingness is what characterizes the void.

It’s this modern paradox between presence and absence that inspired Pope.L’s Hole Theory, where not-ness generates the conditions of a radically new performance of being. In it, he writes, “The successful negotiation / of holes (or should I say hole?) / is dependent on maintaining / a healthy respect / for what cannot be seen. / A voodoo of nothingness.” Slip too far toward the hole; you will lose yourself. Deny the hole; you will lose touch with life’s animating mystery.

Like Pope.L, Anne Carson plays the edge of the hole. In her work Eros the Bittersweet, based on close readings of ancient Greek literature, Carson asks, "Who is the real subject of most love poems?" and responds, "Not the beloved. It is that hole.” For both Pope.L and Carson, the hole marks the risks and possibilities of desire, which feels good because it feels bad, or feels bad because it feels good.

The paradox of the black hole as a hot body of pure nothingness and concentrated everythingness makes for a mighty metaphor — one with real implications. Folding together philosophical and mathematical hole-ideas of the 20th century, Karen Barad expounds an interpretation of the black hole as a location of intra-action, where unlike entities mingle, flirt, and coalesce. It is within this field of encounter that Barad stakes a theory of agential realism: the idea that nothing exists without everything else. All the while, holes appear ambivalently — from nightclub darkrooms to groundwater cenotes, asphalt potholes, and the porous surface of our very own skin.

While the hole presents us the image of nothingness, it is that very ontology of not-ness that makes everything else possible. Holes allow for a cyclical transformation between what is and what is not. Anything from amorous desire and anaerobic respiration to the writing of words and the creation of the universe comes from holes. For example, this is a hole. How do we know such to be true?

Edge

One only knows the hole for its edge. The event horizon, for example, is the surface of the black hole that defines our understanding of this cosmic entity. At this boundary, the velocity needed to escape the black hole exceeds the speed of light, which is as fast as anything goes. Whatever passes through the event horizon cannot pass out of it. Everything enters, nothing exits – even light. What happens after the event of matter’s passage through that edge is one of our greatest mysteries. Everything within is unknown, while everything without may be known or not.

To understand the hole we must trace its edges. Tracing notices the self and its limits in relation to an object always apart. By tracing the edge of what I may know with my physical senses, I am brought into direct relation with what lies beyond my immediate perception: the hole that is always out of touch. “To reach beyond perceptible edges — toward something else, something not yet grasped,” Carson writes, is how we love, how we write, and how we know.

The sensual experience of the edge is what makes the issue of boundaries so risky yet so full of possibility. “The desire to oscillate between the threshold established between inside and outside” is what makes anything from writing, reading, dreaming, flirting, or fucking an act of desire. In this light, desire is a reach out toward the hole only to meet its edge. Boundaries, borders, limits: the phenomenon of desire is where we may fool around in an indefinitely circumscribed zone. Crucially, the subject of desire wishes to breach the edge — to slip into the hole and fulfill their dream of being of and with the object of desire — at the same time as they fear such a total union.

But is it really possible to breach that edge? What happens when one reaches out to fill the gap between subject and object, reader and writer, lover and beloved? What becomes of them when that gap is filled?

Disorientation

Getting lost is easy. The further one traces the edge, following its contours away from the self, the less one knows where to locate one’s self, or how. The way back is not marked. To get lost we need not forgo our usual orientations, but the directions we expect to get where we want to go. Stumbling into the field at night, under a heavy blanket of clouds occulting the stars, and without artificial lights, there is a broad sense of discomfort in not knowing what lies beyond the immediacy of perception. Where will one’s next step fall? How will the ground under one’s feet react? And what if the terrain reacts in an unexpected way, for instance, giving under the weight of body in a sogginess that makes the next step less effortless than the last?

“Does one’s sense of direction improve, the more one knows?,” asks Anne König in Four Times Through the Labyrinth, “Or is it even harder to find the way when one knows how easy it is to get lost?”

We may choose to follow the path into the daylit forest, yielding to the cleared section that signifies the security of knowing. Obeying the limits of knowledge, we may not know where we are going but rest assured that we will arrive somewhere. We maintain a negotiated proximity with the hole and keep a distance from its edge, moving with the sense of easy orientation.

Yet, “in order to become oriented, you might suppose that we experience disorientation.” Without getting lost, what’s there to find?

At any moment we may choose to leave that path and enter into a landscape that requires a different awareness of signs. Offroad orientation to a direction is made by our ability to read these new markers — the growth of moss, the angle of the sun, the flow of a creek. Leaving the marked path requires us to trace the edges of our sensorium. Possibility is born from the initial risk of following our desire — of accepting the hole of our knowing. New orientations become inevitable. Where we might turn away, we turn into many ways. Getting lost becomes a path to finding ourselves outside of our selves.

Body

Body makes sense. Body contains everything we need to find a way: holes to receive information, passages to transfer data, edges to sense the difference. Body orients itself to the many variables that exist outside, and from within body the work of knowing knows. Body makes a map to navigate the unstable terrain: the terrain that always exists as night in the starry field of impossible desire.

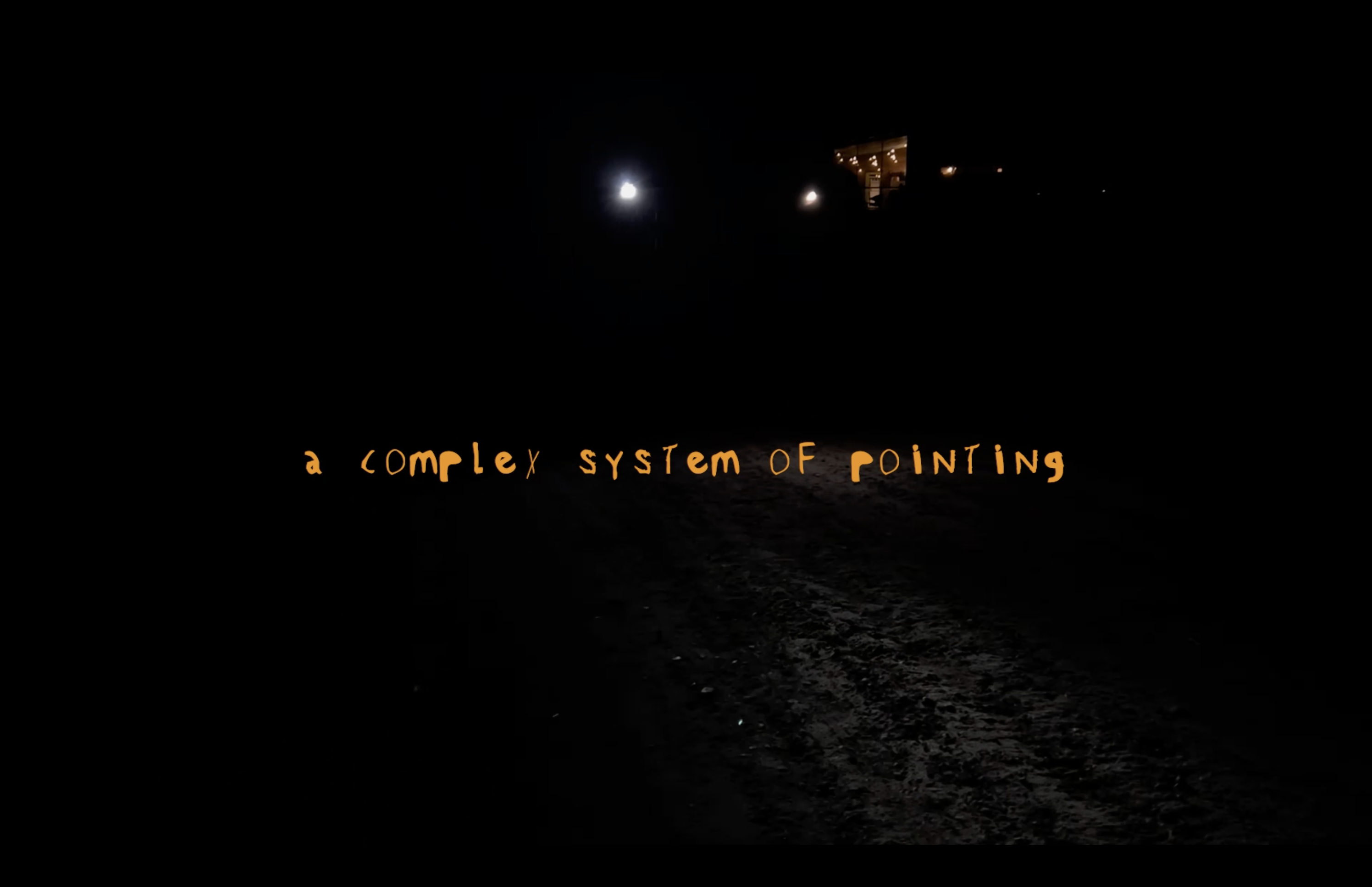

Any way we go, we take body with us. Every action is already embodied, in that body is always already here, never absent even when it is forgotten. To make sense of the unknown ground on which we go, body becomes a hole whose receptive qualities create boundaries and limits: edges that we can trace so that we may know something that otherwise would be not. To evidence the trace of the edge, we must construct “an arrangement to a system of pointing,” which acts as body’s language.

To body we must ask: “How can language index or somehow register in its syntactic and rhythmic unfolding the temporal flux of materiality that makes and unmakes the rich variability of animal, plant, and mineral worlds?” In other words, how might body’s language relate to the intelligence of other bodies within which we exist? Or, what points, with whom, and where?

Without body’s holes and edges — its flesh and blood — there would be no way to receive nor to radiate information. Information, the stuff of orientation, is transfigured into knowledge within body’s matrix in a process we call intelligence. The cool breeze against a sweaty brow, the uneasy reaction in one’s gut microbiome, the feeling of reading wrong words at the right time — such sensations condition our knowing.

Intelligence does not end or begin with body. Where information flows with the sensation of communication, intelligence relates between bodies the edges that define the limit of what may be known, or not. Diverting ourselves from the marked path places our selves in direct communication with outside bodies that provide new clues to the location and composition of the hole. Generating infinite potential arrangements of body in space and time, the hole between us creates the conditions for failure to know anything at all: absolute divine disorientation.

Labyrinth

A labyrinth is a maze of edges centred around a hole. The architectural manifestation of the edge par excellence, a labyrinth takes one down dark corridors, inside deep galleries, and around corners in a series unfolding unknowns that require leaps of fate. A succession of walls direct one’s steps through obscure and opaque orientations. Who navigates a labyrinth is a guest, a lover, an intruder. Sent to find a way without a map, nor knowing what lies ahead, they trust the uncertainty of each step. Who lives inside a labyrinth is the mystery at its very heart.

The labyrinth-idea traces its way back to ancient Crete and is rooted in perversion, greed, heroics, monstrosity, and fear of the unknown. According to the myth, King Minos of Knossos contracted legendary craftsman Daedalus to construct the impossibly navigable maze as a prison to house the Minotaur. Half man, half bull, the Minotaur — known by the name Asterion — was born as retribution after Minos betrayed the sea god, Poseidon. Seeking revenge, Poseidon enlisted Aphrodite, the god of love, to enchant Minos’ wife, Pasiphae, to fall in love with the King’s prized white bull, which Minos’ protected with greed. From the perversity of interspecies desire was born Asterion, who, as Minos’s illegitimate child, was cursed to waste his days trapped in the fabled Labyrinth.

It is said that every nine years, Athens would send fourteen of its brightest young men and women to Crete as sacrifice to the Minotaur — retribution for the death of Minos’s son or Athens’s defeat in war, depending on the source. That is, until the Athenian Theseus volunteered to confront the Minotaur and successfully end the cycle of sacrifice with Asterion’s death. Thesseus slayed the Minotaur, it is said, after a quick battle and found his way out by tracing the path of a red string he tied to his ankle: a “clew” provided by Minos’s daughter, Ariadne.

So much is said about Theseus and Minos, and yet so little of the Labyrtinth’s protagonist, the Minotaur, is known. How did Asterion feel about being removed from his mother and sent to live his days in the depths of isolation? How did he greet the Athenians sent to him every nine years, and how did he pass the years in between? In what ways did he make the labyrinth his home? What brought him joy and how did he experience pain?

We know so little of Asterion because the Labyrinth is everything we are told to fear: the loneliness of isolation, the anxiety of the unknown, the otherness of monstrosity. We know that the fourteen young Athenians enter the Labyrinth every nine years, but not of what becomes of them. Might we consider, not knowing much of the Minotaur, the many possibilities of their fates: death at the hands of Asterion, an obscure survival among endless galleries, a surprising affinity with the resident of the Labyrinth. The myth leaves holes for us, the readers, to fill. As in any hole, nothing is certain, yet anything is possible. We enter the Labyrinth at our own risk.

Works Cited

Ahmed, Sara. Queer Phenomenology: Orientations, Objects, Others. Durham: Duke University Press, 2008.

Carson, Anne. Eros the Bittersweet : An Essay. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2023.

Barad, Karen Michelle. Meeting the Universe Halfway : Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning. Durham: Duke University Press, 2007.

Borges, Jorge Luis. “La casa de Asterión.” Los Anales de Buenos Aires (1956).

Hawking, Stephen. A Brief History of Time : From the Big Bang to Black Holes. Toronto ; Bantam Books, 1988.

Howell, Anthony. The Analysis of Performance Art : A Guide to Its Theory and Practice. London ; Routledge, 2000.

König, Annette. “Orientation / Disorientation: Tati Halle-Neustadt, Debord, etc.” In Four Times Through the Labyrinth. Edited by Olaf Nicolai and Jan Wenzel, 161-232. Translated by Sadie Plant. Leipzig & Zürich: Spector Books & Rollo Press, 2012.

Pope.L, William. “Hole Theory—Parts: Four and Five.” In William Pope L.: The Friendliest Black Artist in America. Edited by Mark H.C. Bessire. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2002.

Smailbegovic, Ada. Poetics of Liveliness : Molecules, Fibers, Tissues, Clouds. New York: Columbia University Press, 2021.

Stein, Gertrude. “A Carafe, That is a Blind Glass.” In Tender Buttons. Mineola, NY: Dover Publications, 1997.